AFP

Around a hundred women have gathered in a community centre in Peshawar, the heart of

Pakistan's fabled northwest -- but they are conversing in a dialect incomprehensible to the

Pashtun ethnic group that dominates the region.

Instead they are exchanging anecdotes and ideas in their native Hindko (literally, "the

language of India") at a conference organised to promote the increasingly marginalised

language.

Pakistan's 200 million people speak 72 provincial and regional tongues, including official

languages Urdu and English, according to a 2014 parliamentary paper on the subject that

classed 10 as either "in trouble" or "near extinction".

According to scholars, Hindko's decline as the foremost language of Peshawar city began

in 1947 when Hindu and Sikh traders left the city after the partition of British India.

Known for its curious aphorisms such as "Kehni aan dhiye nu, nuen kan dhar" ("I'm talking

to my daughter, my daughter-in-law should listen") -- which is meant to convey a harsh

message but indirectly), it only has some two million speakers across Pakistan as opposed

to Pashto's 26 million.

It has also become a minority language in the city of its birth.

"Years and years of political unrest in Pakistan's northwestern region and Afghanistan have

adversely impacted our language and it has lost grounds to Pashto," Salahudin, Chief

Executive of the Gandhara Hindko Board which organised the event, explained.

Some three million mainly Pashto speakers fled war from neighbouring Afghanistan over the

past 35 years, while others are more recent migrants from other parts of Khyber Pakhtunkwa

province.

Loss of culture

The most endangered of Pakistan's dialects are now spoken by only a few hundred people,

such as Domaaki, an Indo-Aryan langauges confined to a handful of villages in remote

northern Gilgit-Baltistan.

Even regional languages spoken by tens of millions like Sindhi and Punjabi are no longer as

vigorous as they once were.

"There is not a single newspaper or magazine published in Punjabi for the 60 million-plus

Punjabi speakers," wrote journalist Abbas Zaidi in an essay, despite it being the language of

the nationally revered Sufi poet Bulleh Shah and the native-tongue of Prime Minister Nawaz

Sharif.

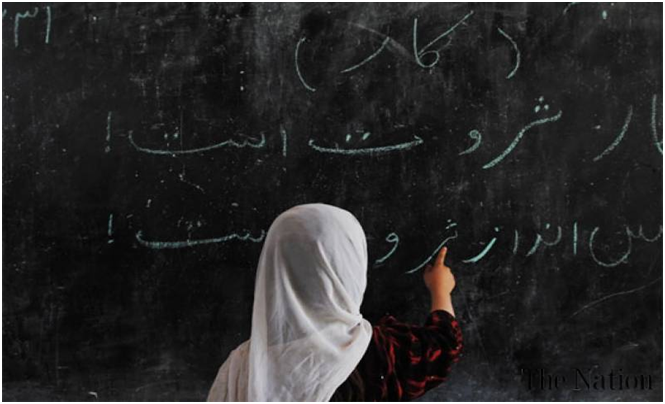

English has been seen as the language of the elite in Pakistan since the country was founded.

It is used at the highest official levels, despite the fact this excludes the majority of Pakistanis

-- many of whom, as a consequence of low literacy rates, do not speak English well or at all,

according to leading linguist Tariq Rahman.

Urdu, the most common national tongue and spoken as a second language by the majority of

Pakistanis, has been relegated to the middle- and lower-level halls of power, while the widely

spoken regional languages -- usually native to their speakers -- are not even taught in schools.

"The result is an underclass that remains out of any public policy making, its upward mobility

increasingly limited, and harbouring a deep sense of inferiority," wrote Urdu poet Harris

Khalique in a research paper.

"A majority of Pakistanis is unable to recognise car registration plates, many road signs that

are only in English, the signboards of shops and offices."

Taking a stand

Some language activists have taken a stand, such as Rozi Khan Baraki, a champion of the

Urmari language of South Waziristan tribal zone that claims some 50,000 speakers.

At its peak in the early 16th century, the language flourished across much of Afghanistan and

what is now northwest Pakistan.

"But then people in [the area] began speaking Pashto and Persian because many of the

speakers of those languages migrated to the fertile lands of this region.

"Migrations have also threatened our next generation, who being Internally Displaced People

(IDPs) in Dera Ismail Khan, Peshawar, and Karachi have stopped communicating in their

mother tongue."

Baraki said to avoid extinction, community elders have asked their people to "force their

children to speak Urmari at homes, especially those who have married women who speak

other languages".

"Our next generation is threatened, this language is going to die if we don't preserve it today,"

he said.

Rahman lauds such efforts but says the process of saving dying languages can only happen

when it is taken up at a governmental level as was the case with Welsh, a regional language

of Britain.

A loss of diversity can have lasting ill effects, he warns.

Those who shift from their mother

tongue to assimilate "try to become clones of another group -- the one which they want to

imitate, and lose respect for their former group," he said.

Children find it difficult to communicate to their elders, while folk stories and music can also

fade from memory.

"There are names of herbs and local names for fruit and animals that are lost. In some cases

when you lose the name of the herb the use is also forgotten," he said.

Source:The Nation, January 06, 2017

Taj Nabi Khan

About 6,000 different languages are spoken around the world. The Foundation for Endangered

Languages estimates that between 500 and 1,000 of those languages which are spoken by

only a handful of people. Thus every year, the world loses around 25 mother tongues. That

equates to losing 250 languages over a decade.

Pakistan has been and is still rich in lingual diversity. Even today, it has more than six major

and 70 small languages. This language heritage provides the country a reliable source of

cultural strength and diversity. However, Pakistan as a federation did not treat the diversity

to increase the social capital but tried to enact national integration through religio-ideological

hegemonic designs.

Some 28 regional languages including Hindko, Kashmiri, Torwali, Khowar, Shina, Burushaski,

Balti, Wakhi, Pahari, Hazaragi, etc., are in extreme danger of extinction. Some may refer to

these as minor or small languages. Whatever you name it, whatever status or respect you

give it. It does not matter. What matters is the vital role of the mother tongues in shaping

identity and worldviews of the native speakers. First the forces of colonisation, now it is the

power of globalisation and modernity which has endangered the mother tongues of the local

populace.

Interestingly, the language and identity politics recently gained firm grounds in Sindh, Karachi,

Southern Punjab and Hazara region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa linking language with the creation

of new provinces. The issue of language and new provinces, no doubt, has been politicised

over the years. The movements for the creation of new provinces fuelled due the persistence

reservations of these language communities over distribution of resources and unfair dealing

with the regional languages. Since the state favors English and Urdu, regardless of whatever

happened in the past, the languages of the domains of power – government, corporate sector,

media, education etc., are English and Urdu.

The language issue has also divided the society in classes such as “English being the language

of the powerful” and the rest taken as marker of lower status and in some forms “cultural

minors”. In the current situation, it appears that the Sindhis, the Pashtuns and the Baloch

have resisted elimination of their languages while the Punjabi middle class has completely

succumbed to the dominant English and Urdu oriented culture. However, the question raised

by many researchers including Dr. Tariq Rahman, one of the prominent linguists of the

country, is whether we are all collaborating willfully or unknowingly in “killing” our indigenous

languages?

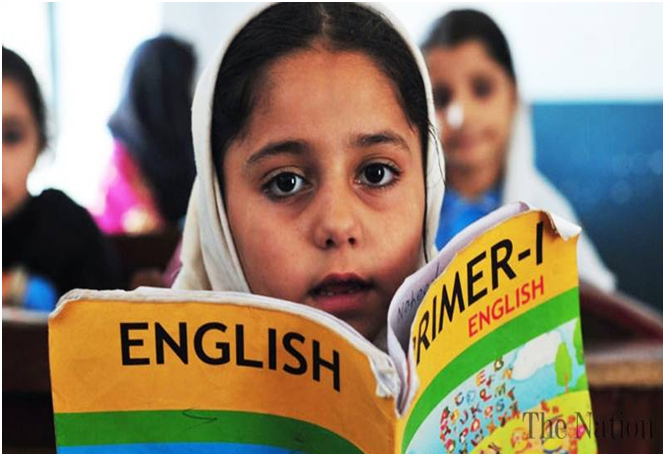

The dominant elites in media are deliberately code switching and code mixing is also affecting

the languages of the region. Similarly, the private educational institutions are contributing to

the extinction of these languages as it has almost become impossible for the so-called

educated youth to purely speak their mother tongue.

The recent episode of the Beaconhouse School System, which is one of Pakistan’s top schools,

has come under fire after calling the Punjabi language ‘foul’ and banning it from usage within

and outside the school premises. The controversial text of the circular has invited strong

criticism from linguists, language students and researchers for imposing ban on the language

which has already been reduced to spoken form amongst its speakers. The English medium

private school’s categorisation of the language as ‘foul’ not only perpetuates colonial stereo-

types, but also reeks of racism.

It’s nothing new all the so elite English medium schools forbid children from speaking any

native language and this is how our so called education system is teaching the children how

to disown their identity. Above all, the notification has numerous grammatical mistakes, which

makes the Headmaster’s authority over the English questionable. Those who are intentionally

becoming part of the same agenda of disassociating us from our mother tongues are actually

breeding a generation who would soon turn their backs on their roots.

We would never be able to acquire the native-like efficiency in English or any other second or

third language but surly the unfair dealing with the mother tongue will make us foreigner to

our first language which is the sole transmitter of our culture, tradition and distinctive human

characteristics.

Let us treat the rich language heritage as cultural assets and not liabilities. It is need of the

hour to change our language policy so as to add English and Urdu to our repertoire of linguistic

skills without destroying our mother-tongues, our authentic selves, our culture and our identity.

The federation is strengthened when minorities feel that their rights, culture, language, and

heritage is being preserved, safeguarded, protected and promoted.

Source:The Nation, October 25, 2016

Shagufta Rehmat Ali

Pakistan is a multiling country and its official language is Urdu. It, indeed, plays an important

role in creating and maintaining collective identity, as it unites the people of all the four

provinces because of its neutrality. Despite this, regional languages are equally important.

Keeping this in view, it has been theorised that a strong relationship exists between language

and ethnicity, since a language represents the culture of a country or region. Against this

backdrop, Pakistan is a country with six major and more than 57 small languages. It is also a

multicultural country, where people from different ethnic identities live together. Most of them

belong to one of the five major ethno-linguistic groups; Punjabis, Sindhis, Pashtuns, Mohajirs

and Balochis. Needless to say, Punjabi is the regional language that is widely spoken (mainly

in Punjab) and, in fact, understood by a large segment of the population across Pakistan.

Pushto is the second largest regional language spoken in the country. Likewise, Sindhi and

Balochi are the two other major languages that give a different ethnic and racial identity to

the people who speak them. These major languages, along with many other small regional

languages, can be used as a tool to integrate or disintegrate the people. More so, all the four

provinces have different cultures. In Pakistan, culture diversity is reflected through language,

literature, art and architecture. All these manifestations together become a part of its cultural

heritage. But, as said earlier, language is a natural and direct expression of any region or

culture. So, regional languages can be the best source of cultural cohesion. Here are some

initiatives that may help to promote regional languages, which, in turn, may expedite the

process of cultural cohesion: Regional festivals must be organised in different parts of the

country to highlight the culture of various regions. For examples, Punjabi folk tales can be

presented in different areas so that other regions/provinces can know about the language

and culture of Punjab. This can be a good source to spread the culture of one region to the

other. Literature can be translated from one language into other language. Media can be

used to promote cultural cohesion as well as regional languages.

Source:The Nation, June 20, 2012

Chauburji

It is divinely ordained that languages were created so that human groups could be identified.

It has been after decades of travelling to places where ‘no urban Pakistani has been before’

and breaking bread with people living there that I have really begun to get a rudimentary

insight into what can be termed as the ‘pathology of a language’.

Traveling up and down the length and breadth of Pakistan by road, one notices an extremely

interesting phenomenon that appears to draw a common thread through linguistic changes.

Many areas of Khyber Pukhtoon Khwa speak Hindko. This is much akin to Punjabi except that

it is quaintly softer in delivery. Move south into northern Punjab or the Potohar and Hindko

changes into Potohari in so subtle a manner as to be hardly noticeable. Southwards into

central Punjab another (and almost discreet) change manifests itself. Before a Hindko or

Potohari speaking individual realises it, he is conversing effortlessly with a Lahori or a native

from Faisalabad. Move down into southern Punjab or the Saraiki belt and the dialect used up

north changes to a rhythmic one that is a pleasure to hear. A discerning person will however

detect the presence of some words herein that sound like Sindhi. This impression is reinforced

when one hears a chaste Sindhi dialogue. This subtle or overlapping transition of language

zones is something that makes the study of how people communicate so absorbing.

Languages have other fascinating characteristics. For example Urdu (a derived word meaning

a gathering of people or ‘lashkar’) was created as a result of putting together words from

Sanskrit, Persian and Turkish (to name a few). I was however amazed, when a Pukhtoon friend

informed me that Pushto was a chaste language with a vocabulary that refused to incorporate

any English word e.g. ice cream in Pushto is ‘yakh malai’. I am currently researching this claim

and my findings so far are pointing to the fact that my friend was perhaps speaking the truth.

Some languages develop idiosyncrasies of their own. Many of these ‘local dialects’ are perhaps

due to the isolation of these language users in a specifically ‘confined’ social or traditional space.

Take the residents of the walled city of Lahore, who can be immediately recognized by the use

of the ‘rolling R’ or the Pukhtoons of Quetta, who use the Pushto alphabet ‘Sheen’ instead of

‘Kheen’.

Languages, especially ones spoken abroad can sometimes get you into trouble. I remember, the

manager of the hotel I was staying in somewhere in Northern Tehran, telling me never to use

the Urdu word for cucumber as it might get me into an embarrassing situation. The French

sentence construction is such that when translated into literal English, it turns the sentence

topsy-turvy – for example the simple greeting of ‘How are you’ or ‘Comment Allez Vous’ in French,

when translated literally into English turns out to be ‘How go you? (I can see the blue line under

‘go’, on my screen telling me that the syntax is wrong).’

The use of the word ‘chaste’ is very apt in the case of languages, as the spoken word does get

corrupted under external influences. I often play a game with my friends and family. I wager with

them that if they can speak chaste Urdu without using any English word for a mere five minutes,

I will pay them a certain sum of money or take them out for a treat. I then engage the individual

in a conversation that he or she cannot avoid and watch as the victim squirms and then gives up

with a huge sigh of relief. In one case, a nephew of mine broke out in tears and later told me that

I had subjected him to the worst torture in life. To me this is a distressing situation, simply

because it is akin to sounding the death knell for the chastity of a language.

Source:The Nation, April 02, 2017

Send email to nazeerkahut@punjabics.com with questions, comment or suggestions

Punjabics is a literary, non-profit and non-Political, non-affiliated organization

Punjabics.com @ Copyright 2008 - 2018 Punjabics.Com All Rights Reserved

Website Design & SEO by Webpagetime.com